However, there were other important countries in the world during the 1800s and early part of the 1900s. Not least of these was Imperial China, which unfortunately spent much of the century seeing its traditional government and culture flow away like the Yangtze River in the face of increased European influence.

Imagine if you will the scene at the start of the 1800s. China considers itself the preeminent power in the world, and forces all Europeans to trade in one place -- the port city of Guangzhou (

or Canton) -- and only with one of about a dozen co-hong, firms authorized to deal in "barbarian" goods. Any gifts brought to the Chinese court by the Europeans were considered tributes that the Emperor may or may not choose to acknowledge. To say it a different way, the Chinese considered themselves the lords of the manor while everyone else was just a serf.

or Canton) -- and only with one of about a dozen co-hong, firms authorized to deal in "barbarian" goods. Any gifts brought to the Chinese court by the Europeans were considered tributes that the Emperor may or may not choose to acknowledge. To say it a different way, the Chinese considered themselves the lords of the manor while everyone else was just a serf.The thought that the Europeans, and the British especially, would want to be treated as equals didn't even cross the collective mind of the Chinese government. China was the Middle Kingdom and everyone else was an inferior barbarian. This of course didn't sit all that well with the British. It didn't help that a whole lot of British silver was flowing toward China because of the English love for tea. Exports of tea from China to Britain grew by a factor of 30 between 1720 and 1830. To recoup all the money being spent on tea, the British East India Company needed to find a product they could sell to the Chinese.

That product was opium. The massive opium trade the British began in China would eventually lead to the First Opium War of 1839 to 1842, which sparked to life (ostensibly) after the Chinese government ordered 20,000 chests of opium burned at the docks in Canton. At left is an image of a sea battle during the war.

From a website hosted by the University of Maryland:

"In 1839 the Qing government, after a decade of unsuccessful anti-opium campaigns, adopted drastic prohibitory laws against the opium trade. The emperor dispatched a commissioner, Lin Zexu (The British Navy trounced the Chinese fleet easily, and the Treaty of Nanjing ended the war in 1842. As a result of their decisive victory, the British gained Hong Kong, access to mainland China via a total of five ports, a HUGE indemnity from the Chinese government to cover the cost of the war, and the abolition of the co-hong merchant guild system. It also meant the government had to accept foreign powers on equal terms, and passed the responsibility of quelling rebellions onto the Chinese gentry.1785-1850), to Guangzhou to suppress illicit opium traffic. Lin seized illegal stocks of opium owned by Chinese dealers and then detained the entire foreign community and confiscated and destroyed some 20,000 chests of illicit British opium."

The newly-gained British position in China set off a flurry of "me-too" sentiment from France, Russia, Germany, Japan, and others for similar concessions -- chief among these being the most favored nation status that gave them the same rights as any other country with spheres of influence in China. The European powers also wanted extraterritoriality, which means that the citizens of Britain could live in China under British law and not Chinese law. This effectively insulated the European nationals from the Chinese justice system.

It of course didn't help that the native population of China was 400 million due to new crops from the Americas and the very, very well-managed agriculture of the Ming dynasty or that the Qing dynasty had recently failed in its flood control measures in the post-Opium War years. This unleashed huge amounts of flood damage and food shortages on the populace.

Tie all this together, and you eventually come to the Taiping Rebellion of 1850 to 1864, when the peasants revolted under the leadership of a frustrated scholar named Hong Xiuchuanwho claimed he was the brother of Jesus Christ. "Hong inspired his followers with a revolutionary fervor that banned alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, held property in common, and called for the equality of all, including women. His movement swept over much of China before the government finally crushed it with foreign help. (from The Flow of History)"

The Second Opium War (1858 to 1860) occurred smack in the middle of the Taiping Rebellion years, and resulted in the sacking of the Summer Palace in Peking (the capital) by British colonial troops stationed in India. It's because of this event that the Bengali word "loot" joined the English lexicon.

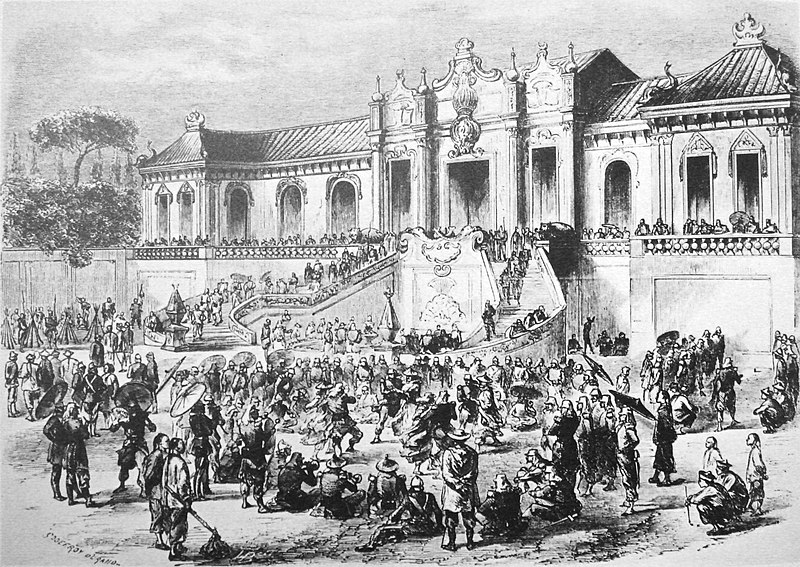

At right is an image of the sacking of the Summer Palace by the joint forces of Britain and France in 1860. The palace would eventually be ordered destroyed by Lord Elgin, the British High Commissioner to China, in retaliation for the torture and execution of European and Indian prisoners (which included two British envoys and a journalist for The Times of London).

In the aftermath of the Opium Wars and the various rebellions beyond the Taiping came the Self-Strengthening Movement, which attempted to graft Western institutions and innovations on to traditional Chinese culture. Needless to say, the strength of Confucianism in the Chinese bureaucracy of the period made any attempt at modernization nearly useless. Between 1861 and 1894, the movement attempted to bring China fully into the Industrial Revolution. However, because of the aforementioned orthodoxy, the Chinese didn't recognize the validity of the political institutions or social theories that helped Europe and the United States become the industrial powerhouses they were.

Adding insult to injury was the carving up of Chinese territory. Britain took Hong Kong and Burma; tsarist Russia took Chinese Turkestan and part of Northern China; France took Cambodia, Vietnam, and Annam; in the post Sino-Japanese War era, China had to cede the Penghu Islands and Taiwan to Japanese control, and even Germany and Belgium gained spheres of influence in the country.

The end of Imperial China wasn't assured until the Hundred-Day Reform of 1898 was ruthlessly squelched when Dowager Empress Ci Xi staged a coup d'etat against Guangxu, the Qing Emperor, who'd been attempting to modernize the country. The Dowager Empress took over the country and, rather than improve things, she spent most of the country's money on a lavish lifestyle for herself.

With the anti-Christian and anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1900, China was once more plunged into a war that ruined its fortunes and resulted in the execution of dozens of high-ranking officials and a requirement that the Chinese people pay war reparations to the European nations whose establishments were attacked during that period.

Imperial China would officially come to an end 11 years later, when Ci Xi was bounced from the throne room and Republican China was born.

6 comments:

This is a great post! I think the Western world still ignores China- there were some comments at Gary Corby's blog a few days back about the lack of mysteries set in China. It's a rich culture- I had never thought of steampunk in China before reading this!

Imagine what stories would emerge, if the focus comes down on China in a steampunk world as it tries to adopt the new technology and ways of the Western countries. It would be grand. :)

Matt - This was really interesting! I haven't been on your blog (or anyone's) for SO long. Love the new look! Please tell me what's going on with you? Any new developments?

I know you've read The Warlord of the Air by Michael Moorcock. You totally should also read Flashman and the Dragon. Not steampunk, but very accurate description of the Peking Expedition.

Random, but fascinating! :)

Fascinating post--I'm all fpr Chinese steampunk :=)

I always find it fascinating (in a horrifying kind of way) to see China slide into a rut during the Ming and the Qing--going from a position of power and technological superiority over the West to the point where their own Summer palace got sacked.

Just one point, though: the Chinese didn't actually occupy Vietnam for long. Lê Lợi threw them out in 1428, and they mostly never came back, though the Qing dynasty did interfere in internecine Vietnamese fighting a few times. From the 18th-19th to the French invasion, Vietnam was split, but very few Chinese were involved.

Post a Comment