The Doble Steam Motors Company released the Model E in 1924. At the time, it was one of the most advanced cars on the road, with the ability to go from 0 to 75 mph in 15 seconds. The Ford Model T of the same year took 35.8 seconds to accelerate up to its top speed of 42 mph.

A 1924 Doble Model E that was restored, in 1994, by

A 1924 Doble Model E that was restored, in 1994, by

Wm. Olds & Sons Pty. Ltd. of Australia.On top of this, the Doble Model E could run for 1,500 miles before its 24-gallon water tank needed to be refilled (including in freezing weather), emitted no exhaust because of the included condenser, and didn't need a drive shaft, transmission, or clutch as the engine was incorporated directly into the rear axle.

The driver's side of the Doble Model E.

The driver's side of the Doble Model E.

Looks almost modern, doesn't it?Perhaps the most surprising thing about this is that an 80-year-old unmodified Model E can pass today's stringent emissions standards. The fuel is burned at a high temperature and low pressure, which means that everything's used in the super-efficient flash boiler.

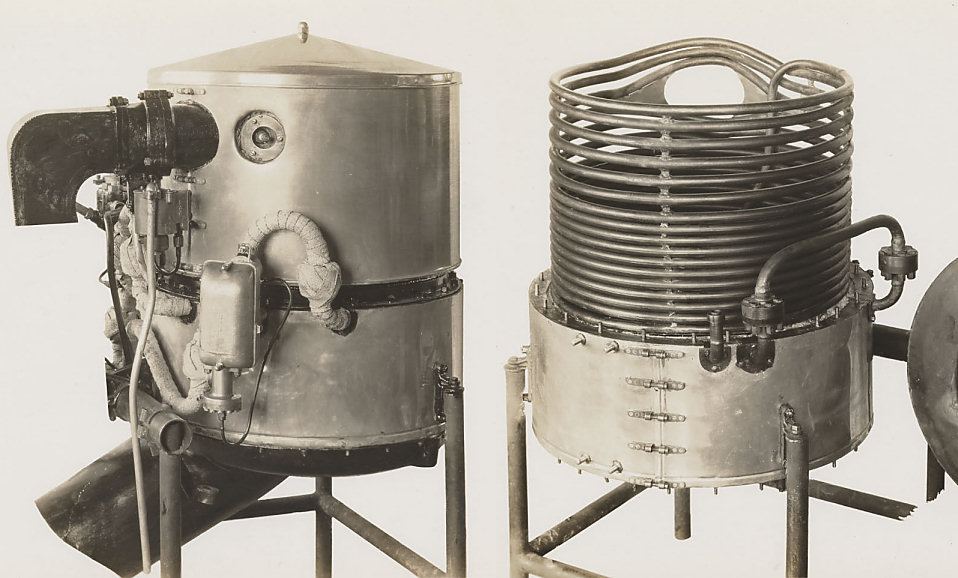

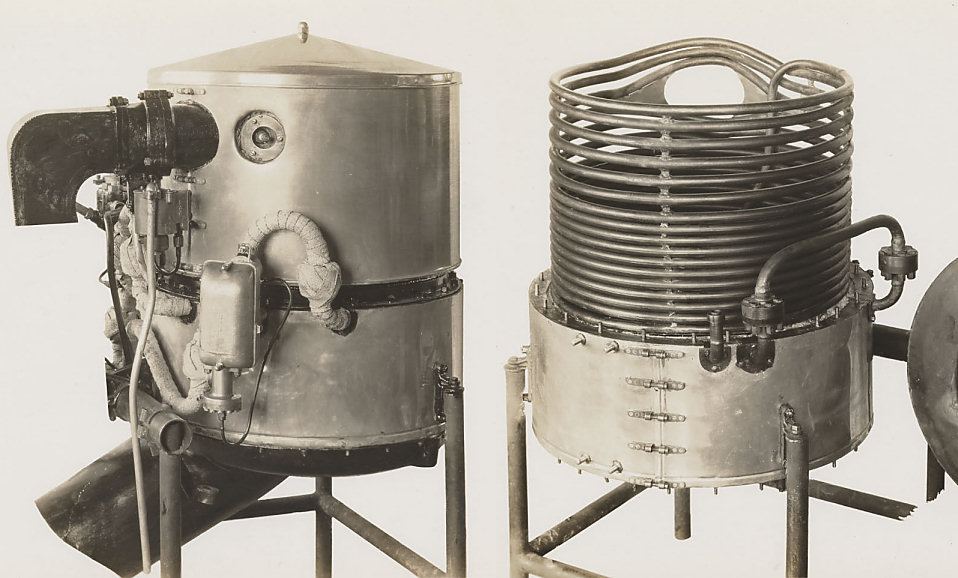

The Model E's flash boiler

The Model E's flash boiler

For a video where Jay Leno talks about his 1925 Model E, head over to

Jay Leno's Garage. He goes into a lot of technical detail about the operation of the car and Abner Doble himself as well.

DamnInteresting.com talks about the Model E's 1924 road test in New York City:

"At the turn of the key, the boiler lit with a throaty burst reminiscent of a gas furnace, and the gauges began to twitch. The boiler reached its operating pressure inside of forty seconds, and the driver experimentally turned the throttle knob on the steering wheel. With a low hum, the car’s steam engine briskly pushed the vehicle forward with 1,000 foot-pounds of torque, smoothly accelerating the car and its four passengers to forty miles per hour in just just 12.5 seconds. As they drove the test vehicle further, they found that its evenly-distributed weight lent it surprisingly good handling in spite of its great mass. The onlookers were understandably quite impressed. The only notable shortcoming was its mediocre braking performance, but this flaw was eclipsed by its massive, silent power and graceful handling. It seemed that the the Doble brothers were finally following through on their promise of a great steam car."

With all the aforementioned benefits to steam cars, you might be wondering why we're not driving them today. Well, there were two problems: 1) Steam cars were $18,000 a pop in 1924 ($224,805.47 in 2008 dollars), and 2) Abner Doble was a perfectionist who was perpetually tinkering with his vehicles. No two Model Es are precisely alike, and this means that the cars never actually went into production.

The cars do look really cool though, and are easy to drive/describe. For the writer of historical steampunk, you might need only mention the name Doble to create the proper veracity in setting (provided it's the 1920s in your story). For the writer of fantasy steampunk, this solves the problem of where to put the boiler and the exhaust quite nicely (because, you know, there isn't any) .

.jpg)