Prior to Whewell's creation of the term, those few men who investigated the world around them were known as either "natural philosophers" or "men of science." Even that's stretching the definition though, as natural philosophers tended to only craft theories and not perform rigorous experiments to prove their theories. Men placed in the pantheon of scientific achievement, such as Aristotle, saw no need to test their thoughts about the world. Instead they merely crafted the theories and let them stand as is. It wasn't until Alhazen's Book of Optics, written between 1011 and 1021 C.E., that a basic form of the contemporary scientific method was even introduced.

Fast-forward to the 1500s, when Francis Bacon championed inductive reasoning -- conclusions reached by experimentation -- that Europe slowly began getting on the proverbial bandwagon. Even then, the most common form of scientific inquiry was still the deductive reasoning of Aristotle. Bacon stridently rejected the a priori (independent of experience) reasoning that the Church carried through from the ancient natural philosophers and such famous Christian thinkers as Saint Anselm and Thomas Aquinas. Instead, he focused on empirically gathering information from the natural world.

"There are and can be only two ways of searching into and discovering truth. The one flies from the senses and particulars to the most general axioms: this way is now in fashion. The other derives axioms from the senses and particulars, rising by a gradual and unbroken ascent, so that it arrives at the most general axioms last of all. This is the true way, but as yet untried."-- Francis BaconOf course, Bacon's methods didn't really begin to gain traction until Robert Boyle (of Boyle's law fame) wrote his 1686 work called A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature. Inductive reasoning quickly gained prominence after Boyle's work, even though the sciences remained lumped together under the phrase "natural philosophy."

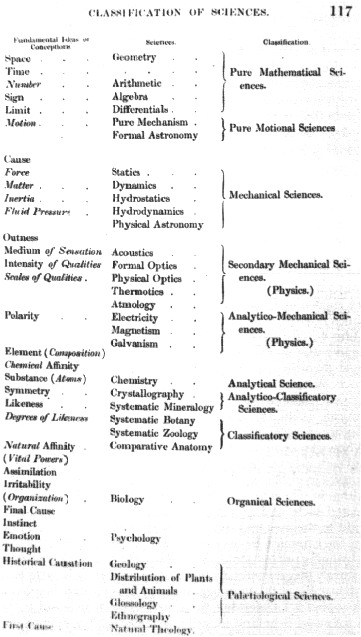

It wouldn't be until around Whewell's time that the scientific method became its modern form, and scientific investigation took on a more divided form. It was actually Whewell himself, in his Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences (1840), that classified the field of scientific inquiry into the divisions we know today.

Whewell's classification of the sciences (from VictorianWeb.org)

This classification system, and Whewell's authorship of one of The Bridgewater Treatises, cement his place in the scientific pantheon. He also famously opposed the concept of Evolution, publishing an 1845 book called Indications of the Creator, which refuted Charles Darwin's theories.

You might perchance be wondering why this all matters to a writer of Steampunk fiction. Truth be told, it's more a matter for the writer of historical fiction set in the years before or immediately after 1833. But, seeing as a lot of Steampunk is alternate history, the fact that the word "scientist" didn't exist until Whewell came up with it is an important thing to note. You can't use the word "scientist" in a pre-1833 story because the word didn't exist then. Also, it wasn't until the 1830s that men of science began to specialize in a set discipline. In other words, it was excessively uncommon for someone to only study biology, or chemistry, or physics before Whewell's period.

Taking this to its (somewhat) logical conclusion, the splitting of science both during and after Whewell's active period means that the writer of alternate history Steampunk needs to take care with what time frame they set their story in. Even though the story is alternate history, that's no reason to use words that didn't necessarily exist in that timeframe, unless you can come up with a very good explanation (and really, "natural philosopher" serves perfectly well for "scientist" for pre-1830s stories. Gives you the writer more freedom.).

8 comments:

You, my friend, are definitely a man of science. Nicely done.

Yes, definitely a man of science, and research. You amaze me.

Wow, interesting! I really didn't know the date at which 'scientist' became a known word.

Research king!

Michele

Southern City Mysteries

Oh, yeah...my diary entry will be up in the AM!

Michele

Southern City Mysteries

Okay, the middle of that list is full of interesting fields, but the top makes me want to gauge my eyes out- memories of high school classes come flooding back. And it isn't pretty!

Indepth. Reads like a college lesson. Very interesting though.

I was thinking of the Diary Contest as a blogfest for some reason and almost forgot to post.

.........dhole

Very, very interesting!

But to be fair all I could focus on was the twitter convo on your sidebar. Something about buttsing with @writingagain that I REALLY don't want to know about.

I have always loved the term "natural philosopher" and enjoy that my Ph.D. in Environmental Engineering sheepskin says "Doctorate of Philosophy" before any mention of Engineering.

And I've always been fascinated by the progression from generalist to specialist in the sciences, as more and more science has become known/discovered/invented. Back in the day that people were "men of science" or "women of science" (there were a few before Madame Curie, just not many) they were philosphers of many sciences, because the depth of each was so shallow. Also, they were often seen as interconnected.

But as time progressed, science became more specialized. This continues today. My father got his "Engineering" degree in the 1960's - there was no specialization, even then. By the 1980's, I was able to recieve one of the first degrees in "Aeronautical Engineering," a specialty that grew out of the space program, and advances in those sciences. It wasn't until the late 90's that you could acquire a degree in "Environmental Engineering."

In some ways this hyper-specialization loses some of the romance of a well-rounded degree in science - but such a beast does not really exist today. Except among lay gentlemen (and women) of science. :)

Post a Comment